Note, for example, the ways Alexandra Munroe describes the “doing” of Ono’s body as “traditional Japanese feminine” and “masklike”: That is, as critical reception of her performances demonstrates, Ono’s Cut Piece circulates alongside tropes of Asian femininity as submissive and passive, as something to be seen but not heard. 1 Ono’s six performances of the piece, however, evidence the perlocutionary effects of her particular body performing the piece. The unmarked social status of the performer and audience members of the script might be expected to welcome a similarly unmarked interpretation of the performance within a genealogy of participatory art from the 1960s. I should mention that, as with other event scripts, the subject of the performance is universalized to include performers other than Ono herself. This emphasis on the performer, however, is largely lost upon performance-or rather, in inviting audience participation, the performer’s challenge is to receive not only the participant’s physical cut but also the knowledges that would narrate such an encounter. Since it is imagined that the event script would only ever be initiated by the performer, as an abstract experiment for the imagination, as with arguably any of Ono’s event scripts, the emphasis is on the performer’s experience of the piece and for how such an exercise might expand and enact the performer’s world. One may also note the script’s focus on the performer as grammatical subject. Reading the event script for Cut Piece, one may be struck by the performer’s open invitation to the audience who “may come on stage,” “cut,” and “take” from the performer. I will then turn to Jacques Derrida’s meditation on hospitality to consider how Ono and Derrida challenge and extend one another and, in doing so, contrast figurations of Asian femininity beside an abstract universalized subject. Surveying critical reception of Cut Piece, much of which enfolds Ono into racist and misogynistic ideologies, I suggest that Ono’s own rhetoric of unconditional giving, as embodied in Cut Piece, circumvents persistent Western discourses that conjoin hospitality with female sacrifice and Asian docility.

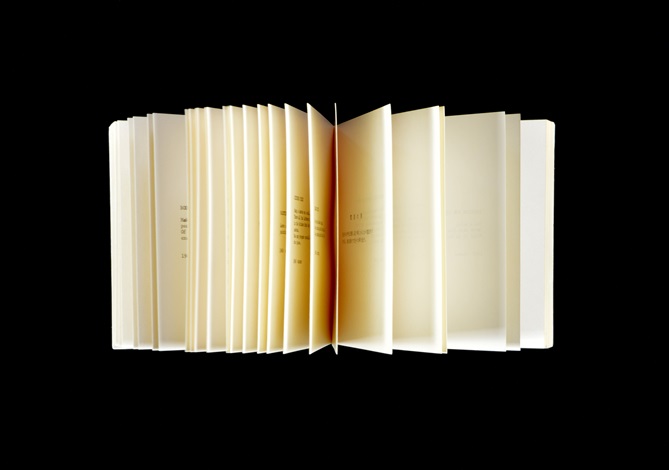

In the first section of this article, I pick up these discourses of feminist performance art and jostle them against a discourse of hospitality in order to theorize Ono’s lifeworks as Asian feminist performances of hospitality. From Julia Bryan-Wilson’s 2003 essay on Cut Piece as a “ritual of remembrance” (103) to Jack Halberstam’s chapter on radical passivity in The Queer Art of Failure, Cut Piece is convincingly presented as epitomic of protofeminist performance art. In one view, Ono’s six performances of her famous event script position her as the host of the performance and her audience members as the guests she invites to the stage who leave with something “to take with them.” Since premiering in Kyoto in the summer of 1964, Cut Piece has garnered renewed relevance and circulation in feminist art historical research and (re)performance of Ono’s event script, including the artist’s own in September 2003 in Paris. Performer remains motionless throughout the piece. It is announced that members of the audience may come on stage–one at a time–to cut a small piece of the performer’s clothing to take with them. Performer sits on stage with a pair of scissors in front of him. Similar to Ono’s other event scripts-as famously published in her book Grapefruit (1964)-the premise of Cut Piece is simple: Yoko Ono’s oft-cited Cut Piece could be described as a performance of hospitality par excellence. Miss Ono sat looking inscrutably Japanese (she is actually Japanese) while members of the audience took turns to cut off her clothes with a pair of scissors. You blow out the candles and serve the cake. You look into the video camera you’ve set up. You light the candles on the cake you’ve brought and remain quiet as the man opposite you serenades you with “Happy Birthday.” It’s not your birthday. You sit in someone else’s eat-in kitchen with your bare feet against the linoleum floor. Your mind wanders to undetermined places but your eyes stay resolute. You are there as they walk around you, look at your body, and cut the fabric layer beside your skin. After your initial invitation, people from the audience approach you, one by one, taking up the scissors you’ve put beside you. You sit on the floor of a bare proscenium stage, looking out to an unlit audience.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)